I began thinking about the fact that I stand in the middle of two opposing forces in the Negro community.

One is a force of complacency, made up in part of Negroes who, as a result of long years of oppression, are so drained of self-respect and a sense of “somebodiness” that they have adjusted to segregation; and in part of a few middle-class Negroes who, because of a degree of academic and economic security and because in some ways they profit by segregation, have become insensitive to the problems of the masses.

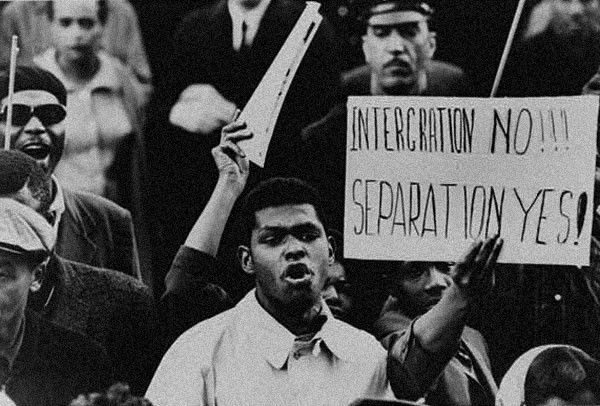

The other force is one of bitterness and hatred, and it comes perilously close to advocating violence. It is expressed in the various black nationalist groups that are springing up across the nation, the largest and best known being Elijah Muhammad’s Muslim movement.

Nourished by the Negro’s frustration over the continued existence of racial discrimination, this movement is made up of people who have lost faith in America, who have absolutely repudiated Christianity, and who have concluded that the white man is an incorrigible “devil.”

I have tried to stand between these two forces, saying that we need emulate neither the “do nothingism” of the complacent nor the hatred and despair of the black nationalist […] If this philosophy had not emerged, by now many streets of the South would, I am convinced, be flowing with blood.

And I am further convinced that if our white brothers dismiss as “rabble rousers” and “outside agitators” those of us who employ non-violent direct action, and if they refuse to support our non-violent efforts, millions of Negroes will, out of frustration and despair, seek solace and security in black nationalist ideologies — a development that would inevitably lead to a frightening racial nightmare […]

If one recognizes this vital urge that has engulfed the Negro community, one should readily understand why public demonstrations are taking place. The Negro has many pent up resentments and latent frustrations, and he must release them.

So let him march; let him make prayer pilgrimages to the city hall; let him go on freedom rides -and try to understand why he must do so.

If his repressed emotions are not released in nonviolent ways, they will seek expression through violence; this is not a threat but a fact of history.— Martin Luther King, Jr, Birmingham Speech From Jail (1963)Brandon Webber

Black people protesting in favour of establishing a Black separatist society.

For four hundred plus years — in any and every way, the oppressed have articulated this sentiment in the past, as well as how the oppressed word it now, come to the same, disquieting result.

That result is the continuation of how long Black people have been oppressed in this country. The innumerable amount of Black people who have been taken by this colonial settler, cis-hetero patriarchal, imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist, militarized-police, the surveillance state is staggering.

Though Black people (activists, artists, philosophers), alike, have participated in this prolonged fight using a diverse set of tactics (through the direct action of Malcolm X, to the keen and emotive persuasion found in James Baldwin’s writing on whiteness itself), we have also, in many cases, overlooked, but have inevitably seen the outcome of this continued oppression manifested in the resolutely reactionary politics of Black nationalists.

As most of us understand basic levels of human psychology and sociology — philosophy, or what have you, there comes a time, where, if and when a people’s cultural, ontic, social, and ethnic identity is obliterated for so long, and receive little to no transformative justice as a result of this prolonged, inhumane system of whiteness, we lose faith in notions of justice, life, and self-hood itself, unless we take on the ethical responsibility of obtaining justice for ourselves.

Through our own methodology. In our own way. By any means. A meme once said: y’all white people lucky muthafuckas don’t want revenge. It’s not racist or means. It’s reality. Unknown to many of y’all, there is actually truth in this assumptive, contradictory claim:

- This is not completely true; and,

- a lot of oppressed Black folk, in fact, do want an alternative form of punitive justice done to whites just as we have been oppressed and executed by them for the sole existential reason of being Black.

Because many of us have already divested our faiths from the imperialist white supremacist government for failure to protect us, many of us have taken up arms (figuratively and literally) in an attempt to procure that we protect our own people.

Strictly through a conservative, traditionalist means, as previously articulated by the NOI (Nation of Islam), pro-capitalist, conservative-leaning Hoteps, the New Black Panther Party, all coincide with a similar line of thought: to develop a Black world, segregated from white people; to establish and possess full control of a Black economy, businesses, arts — Black everything.

On the other end of this political goal, let us not forget that many Black nationalists have like-mindedness in becoming the oppressor — by replacing white patriarchy with Black patriarchy, governed by cishet Black men, who in many cases, have also shared fascistic like-mindedness to neo-Nazis and white supremacists such as Richard Bertrand Spencer and George Lincoln Rockwell of the American Nazi Party founded in the 1960s.

Of course, not wanting revenge might be deemed passive. And so, if revenge is in the hands of the oppressor/avenger, is it still morally and politically unjust? Let us call into question the socio-existential legitimacy of political revenge and political retaliation.

An instance of the oppressed desiring to kill their oppressor is justified, yes. The oppressed wanting to kill a white person, without any constructively collective means to procure (stolen) resources, or other necessities for oppressed people is reactionary.

An overlooked dissimilarity of these acts is their political intentions and impacts beyond political intentions. One is in the vein of political struggle. The other is in the vein of individualist-based vengefulness that hides under a guise of reflexive nationalism. Why is this an instance of “inevitability”?

Well, Dr Martin Luther King, Jr has said that a riot is the language of the unheard. And so, again, we knew of this forthcoming explosion also articulated in Langston Hughes’ quintessential poem, “Harlem”:

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore —

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over —

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

And his more direct and prospective poem, “Warning!”:

Negroes,

Sweet and docile,

Meek, humble, and kind:

Beware the day

They change their mind.

Wind

In the cotton fields,

Gentle Breeze:

Beware the hour

It uproots trees!

To put it differently, Black people have long known of this Afropessimist inevitability. Joseph Winters writes in their article, “Blackness, Pessimism, and the Human”:

What exactly is Afro-pessimism? Who are its proponents? While several authors currently identify with the Afro-pessimist position (Jared Sexton and Calvin Warren, for instance), Frank Wilderson has provided the most acute and well-recognized definition of the term.

In his incisive text Red, White, and Black: Cinema and the Structure of US Antagonisms, Wilderson writes,

“The Afro-pessimists are theorists of Black positionality who share Fanon’s insistence, that though Blacks are sentient, the structure of the entire world’s semantic field…is sutured by anti-black solidarity” (58).

According to this description, the domains of meaning, grammar, and law are defined over and against the black body, which came into being through the gratuitous violence of kidnapping, the Middle Passage, and slavery.

The Afro-pessimist contends that humanism incorrectly assumes that all forms of suffering can ultimately be redressed and overcome through the grammar of rights, respect, and compassion.

To the contrary, Wilderson contends that humanism cannot acknowledge “an object who has been positioned by gratuitous violence — a sentient being for whom recognition and incorporation are impossible” (55).

In other words, humanism is blind to its own condition of possibility because the coherence of the Human relies on the exclusion of Blackness.

Thus, when we contextualize this with the Afropessimistic despair of the Black nationalist, we better understand that many of us Black people are encumbered with an ambivalence that consists of rage, confusion, melancholy. These feelings of ambivalence shift repeatedly.

Who better to encapsulate the material reality Black people experience every day to James Baldwin’s sentiment on being Black in America:

To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time. — James Baldwin

We must not necessarily look at riots at face value, but look at the political nuances of riots, the people who are continually disenfranchised which lead up to these riots, and why riots are a result of an unjust system as well as an unjust place.

A riot manifests itself in multiple ways.

In this way, the Black nationalist deems physically ‘eliminating the oppressor’ as an ideal solution, like from the virulent sentiments expressed by one of the leading members of the Philadelphia chapter-New Black Panther Party, Samir Shabazz’, who stated:

You want freedom you gonna have to kill some crackers…gonna have to kill some of their babies!

Moreover, we’ve seen Black reactionaryism from the likes of the New Black Panther Party’s posthumous, anti-Semitic, anti-LGBTQIA leader, Khalid Abdul Muhammad, who shared similar lines of thought in 1993, in which he had given an inflammatory speech and was subsequently kicked out for his rhetoric.

These are just only two instances of Black nationalist reactionaryism. One reason why the wrath of the Black nationalist is justified is that whiteness is sociopolitically irreconcilable with Blackness.

Whiteness is a nihilist, engulfing, dehumanizing social position; it is not a culture or race. Whiteness exists for the absolute detriment of nonwhite people. It is structural and functions against collective groups on the basis of their skin color.

I have, time and again, been enticed by the lexicon of identity reductionism articulated in Black nationalist thought. Yet, ultimately, I’ve pondered in the back of my mind on several occasions — to what end will this serve me? Serve my people?

Where, or how far will a Black person’s rage go if it only acts on revenge for the sake of revenge?

The only time rage is not conducive to Liberation is when it is used in an individualist manner. Furthermore, this is politically ineffective because it suggests that oppression functions on an individual-to-individual scale. Oppression is not individual.

As Black people, we are past tired.

We are justifiably outraged at the white supremacist establishment — the country in its entirety. One way we can start collectivizing our rage to dismantle these -isms of oppression, is to iteratively check in with our people and how one another is doing because internalized oppression is also very real.