In such thriving times for social media, everything online is designed to stimulate self-expression. Aesthetics have never had more of a key role when it comes to the way we understand one another, having style as the chief form of building one’s identification.

The discourse around it has evolved so much that even our language was shaped into it; we created new words like Cotagecore, Avant Basic and Dark Academia, showing how serious we take self-image as an extension of our lifestyle. In spite of that, it gets pushed out of the conversation what is always underneath all the fabrics and textures: sizes.

Regardless of what fashion trope you find yourself in, how the clothing fits the body can make or break the outfit, going as far as to decide who’s “allowed” to wear it and who isn’t.

With the revival of Y2K for example, where bodies are used as another accessory to flash around, many people are, again, excluded from fashion mostly for this one aspect. As fashion changes with time, it is important to explore more deeply and outside of the consumer spectrum what it means to occupy space.

How did we get here?

First of all: how did we come to know a body as a size 6, 8 or 10? The standardization of apparel’ sizes is attributed to the need for cheaper uniforms for the marine and the army in the eighteenth century.

They had to be made quickly and within a small range of sizes while fitting the largest number of bodies, so it wouldn’t take a sewer to measure a person every time they needed a new uniform and it’s convenient to consult.

Due to how cheap this pattern of production was, its simplicity, and new technologies such as the sewing machine, these ready-to-wear pieces made it into the market and established shopping as it is known today.

Even though the function of sizing has not changed, the word “standard” has gained a broader meaning over time. It has been observed that, over the decades, pieces with the same measurements are being labelled progressively with smaller numbers, creating the praxis of “Vanity Sizing”.

Some studies explain this as a marketing strategy that appeals to the public’s (very fatphobic) vanity since it was reported that people tend to shop in places where they fit smaller cuts.

Others justify it as a needed action to be up-to-date with the general population’s new dimensions. Nonetheless, it has been shown that the targeted demographic is still the main lead, and this allows for all kinds of tendencies: ethnicity, age, job status, race, economic level - a particular study in 2003 says that more expensive stores tend to have smaller patterns when compared to cheaper ones, and so on.

It's fairly easy to witness all of it just by looking at a single person’s wardrobe. The difference of some inches can make you a number 8 in one store and a 12 on the other. Dressing up is a game of compromise: to have the perfect length, you may have to give up on the right waist size, have it tighter around the tights, looser around the knees, and so on.

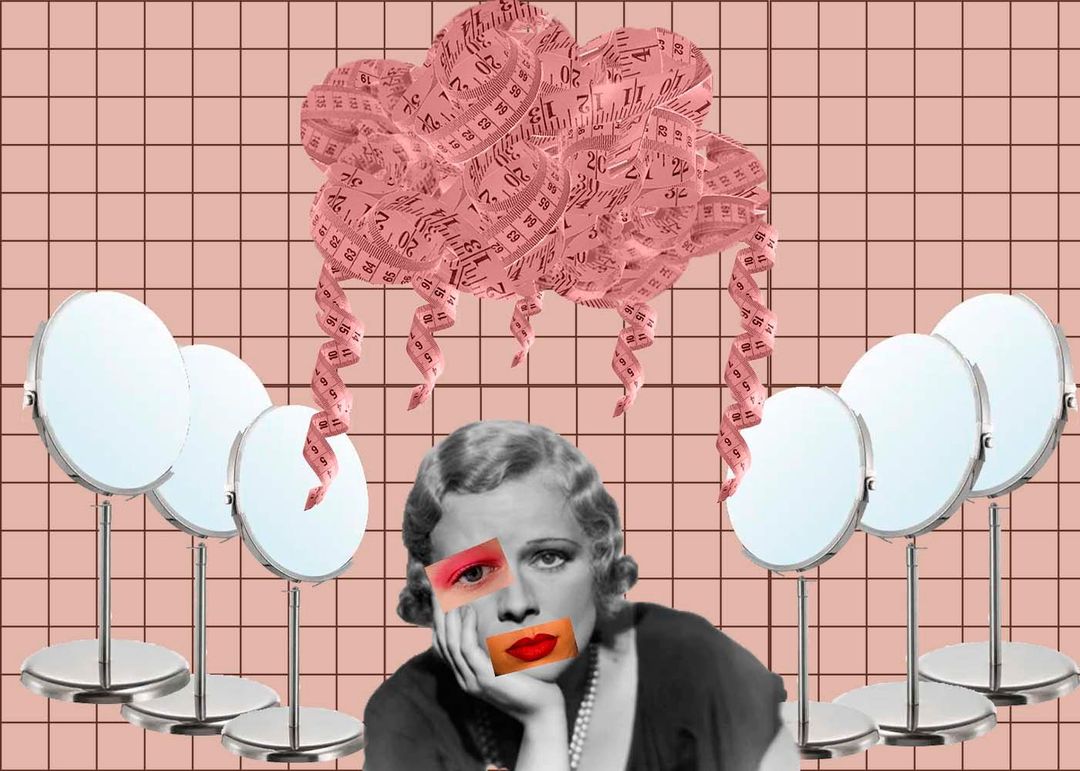

Besides being a major inconvenience when trying to buy anything, these differences can easily distort one’s self-image. How does a person “grow” or “shrink” between two pairs of pants of different sizes, yet, they all fit? What does being a “medium” body really means? Did someone really put on weight or have they just changed stores?

For such an ordinary activity, having the concept of who we are and what we look like changing routinely is a big trigger for body dysmorphia and eating disorders.

All these misleading numbers only have such an impact on the collective subconscious due to our relationship to consumerism. Since it’s culturally acceptable that a person is defined by what they consume, it is nothing but natural for someone to keep track of their features by what they purchase. In spite of being directed to the public, these clothes are made with the companies’ maximum profit in mind instead of consumer’s satisfaction.

We are tricked into accepting to have some of ourselves erased in order to have options around what to wear. When our most recurrent way of interacting with our bodies is by dressing it, therefore consuming apparel, it’s not such a stretch to say that we see ourselves not as how we really are, but how these companies see us: approximations.

Now, imagine how much power those misconceptions have on mental health and body image when catapulted via the internet. We all have seen this: impossible sizes, that weren’t made for people but for companies, are adopted by the handful of people that fit them perfectly and shared between millions.

It becomes a vicious cycle: every time a new trend pops up, the ones that have a better silhouette for the season - generally, the same tall, skinny, white conventionally attractive people - will appear in every possible outlet, and telling ourselves it’s okay to not be like that becomes a meaningless echo in our minds.

Much like collections, bodies are being perceived as cool or not, they go in and out of season, normalizing perhaps the most hostile environment in decades to maintain a healthy relationship with your image.

Clothing sizes don’t mirror body sizes.

Clearly, the weight of it all is unbearable. This consumer culture is so aggressive and detrimental nowadays that in order to shield our minds we must be active deniers. We've come a long way already, popularizing buying second-hand and adopting minimalism, but this is still a purchase-focused approach to us.

While Victoria Secret’s decision to terminate their iconic Angels fashion show and choose people such as Michele Obama as their ambassador is considered a progressive move, it was overdue and certainly made for marketing purposes.

To really break that, time must be taken to recognize ourselves as organisms. It all comes down to the philosophy that slow fashion brings when talking about bodies: they last longer, don't change as fast, and naturally, that should be respected. Buy a measuring tape, take notes and accept your size prior to trying to put them in a box.

Notice what part makes you uncomfortable when showing, what are you most confident in, what would you have to look for in order to find what fits your pros and cons. It's cliche, but holds true: wear your clothes, don't let them wear you. Wardrobe items might change with the seasons, but you are more valuable and complex to believe that the same applies to you.

And when it comes to the flexibility of fashion, holding on to beauty standards only restrains its power to be an identity outlet. Much like speech, you can't know a lot about someone if they only speak in the right read “conventional and broadly accepted”- way.

It's over accents and slang that we bond, much like it is someone’s personal style that makes them stand out. Moulding ourselves usually means to end up not as we imagined, since the standards are unachievable, and mad to our bodies the moment they fail to be what they already are not.

The potential to portray sexuality, politics and genre and the possibility to make part of a group that truly talks to who you are gets thrown away due to the fabricated idea that the pinnacle of beauty is a brand's interpretation of a person and not an actual human.

The lack of curiosity and amicable first contact with our physique creates long term damage to our brains. This industry and its beauty standards were around before us and most probably will maintain its relevance after we are gone, and not even an immense amount of boycotts could redirect their services to the public’s interest, so it’s up to us to take control of ourselves.

Much like slow living, we should be slow sizing, treating our dimensions as something to be dealt with rather than fixed in our everyday life and making space for more productive thinking than hating the mirror’s image.