I’ve previously thought about the ontology of Blackness in America. Although Black people, socio-historically, have long been the laborious, driving force of what created this country, and our socio-historical contributions of what has made this country great, I can’t call myself an American.

As a young boy, while living in Rockland County, New York, I impetuously denounced my Blackness, my Haitianess. For so long, I hadn’t made myself aware that I had been living a life shrouded by internalized colorblind anti-Black racism. I’d proudly say that I was an American, having no cultural knowledge or understanding of the sociopolitical implications of why I said it.

Revisiting and probing the cultural significance of the assertion, “I’m an American”, called into question with significant structural introspection, reveals that the assertion is essentially defined as one who would adopt a position in accepting sheer individualist, white supremacist patriarchal nationalist ideology.

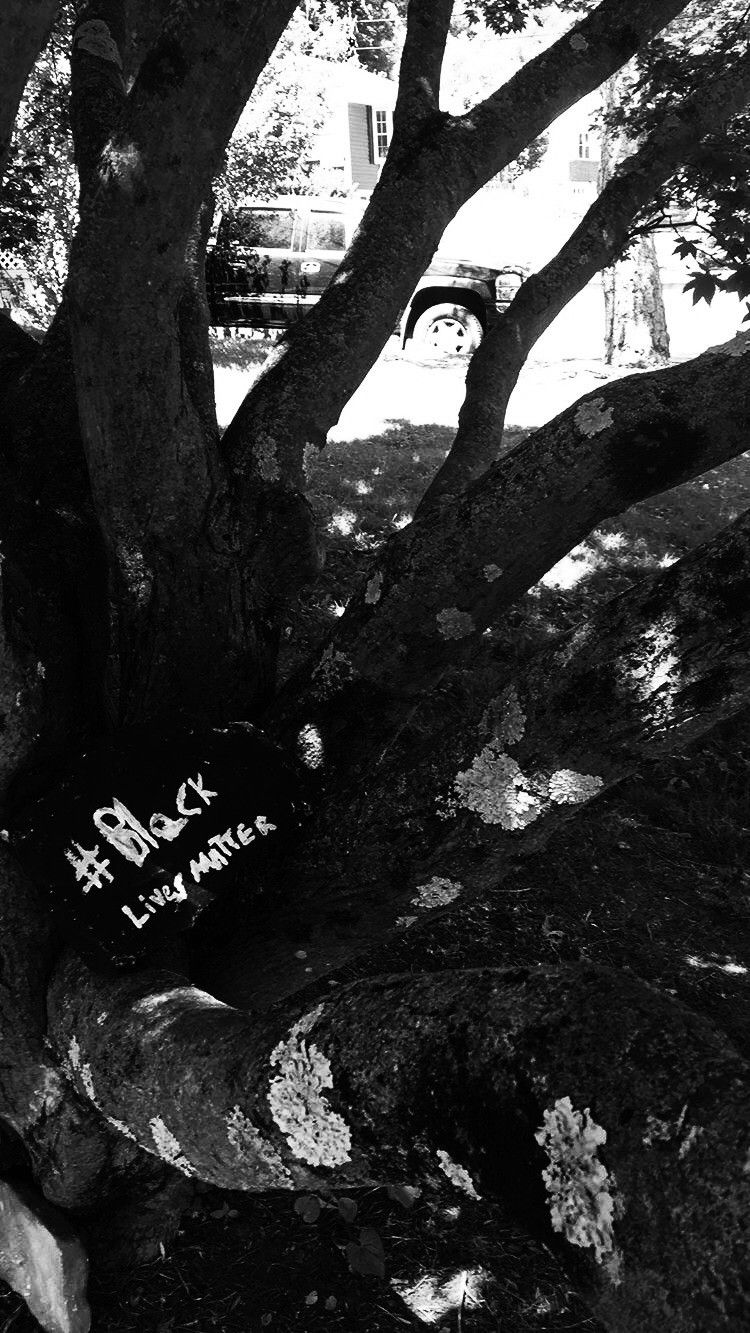

Yet, even in realizing this, and knowing where Blackness is in America, is not my perception of it alone. This stereotypical perception is what stems from the white gaze that posits that all things in the Black imagination — our perceptions, are white, from people to historical events, and Eastern and Western icons. I’ve wondered if whether my discontentment is justifiable or not; however, it is to be called into question, for if it is in my white gaze that I’ve been conditioned to see America in this way, it then poses an issue of ‘ontological determinism’ of Blackness, that is, I mean, in the sense that we, as Black people, might never be able to proudly assert that we are Americans. Between chattel slavery and mainstream capitalist exploitation of Black people, does it make it justifiable to sweep under the rug these socio-historical occurrences and intergenerational trauma brought to Black people of this nation, while still valuing the Black lives whom were forced against our will to fight for this country?

We can call ourselves Americans, yes, and to an extent we know we are, but not if it creates a discomfort in our being, our Blackness, not if the white gaze misguides us to what we were indoctrinated to think we know about America, especially those of us whom are still learning about America’s ills, evils, and lies.

Stereotypes Black folks maintain about white folks are not the only representations of whiteness in the black imagination. They emerge primarily as responses to white stereotypes of Blackness. — bell hooks, black looks: race and representation

Revisiting this text and unpacking the feelings I have held in opposition to whiteness, as perhaps being harmful in itself, it is harmful, not because whiteness in itself is not ubiquitously terrorizing to all life, but because, as a form of retaliation, repudiating whiteness, is again, in a way ascribing to the white gaze in my imagination.

Among some of the fragmented questions that come and go, I ask myself whether or not I choose to foolishly declare myself an American because of how the white gaze augments my assessment of America’s nefarious history, or is it America and the American flag alone that holds its shadow of colonialism, systemic genocide, and domination dear to itself as its so-called “honorable tradition” — what the neo-Confederacy, white American nationalists, and neo-Nazis all bear a symbiotic, homosocial bond of vainglorious whiteness to? A vainglorious whiteness that these white men and white women have arrogantly desired to lose their bodies for to destroy Black bodies like mine, and all those who are not, all because they believe their whiteness is integral to their being.

I do not devalue or denounce the sociohistorical contributions of all of us who are oppressed to not call ourselves American. Nevertheless, how can I ever come to be proud of pledging under Francis Bellamy’s universalist and racist allegiance? To a country that demands I honor that — that denies I am an American-born Haitian — to a country that wants me and all people who look like me, to be killed?