When news was first trickling out of Wuhan about the outbreak of a novel coronavirus, I was under something of a malaise. Working in hospitality over the busy Christmas period had drained me of all the energy I’d hoped to pour into Black Friends, and the other creative projects I’d fumbled my way into. The New Year celebrations had passed me by, and I felt I had no confidence in my plans for the future.

But it was on the eve of Chinese New Year, before we understood the severity of the virus that I was complicit in an act of everyday racism, which would lead me to question my continued commitment to this platform.

‘It’s the Chinese students coming over here that are putting us at risk of these diseases. You see them walking around with their masks on. They’re very dirty people. I wouldn’t be going to a Chinese restaurant if I were you, there’ll be loads of them there!’

As my Uber driver utters these words, I lock eyes with him in the rear-view mirror and nod in agreement.

It’s not the first time I’ve done this. Growing up in predominantly white spaces meant that from an early age I quickly developed a sense for code-switching. And as a result, whenever I encountered unwanted confrontations, it was easy for me to save face by consenting to ideas, or opinions, that stood in stark contrast from my own.

But now the stakes were different. I’d graduated from university, travelled across borders and continents, and learned how to vocalise the way I understood the world - or so I thought.

The moment I showcased my approval of his words, I could feel the guilt rise up within me. Yet in spite of my moral convictions, I continued to gesture in support. It was as if I was undergoing some kind of out-of-body experience. As if for some brief moment in time I was playing a different version of myself.

One that I knew would last only as long as the car journey that bound us together, but to him would last an eternity.

Before long, he dropped me off at my destination, and I entered the restaurant surrounded by the faces of those I’d openly discriminated against just moments earlier. And as I sat there in the company of friends, enjoying the food and hospitality of the staff who worked so tirelessly to enrich my evening, I sank deeper into the confines of my hypocrisy.

In the weeks that followed, when I would read about cases of xenophobic behaviour towards Chinese and East Asian peoples in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, I couldn’t help but think of that incident in the taxi.

I wondered if my double standards could be attributed to the rising tides of anti-East Asian sentiment that are sweeping across the UK, and other parts of the world. If there were others like me, who were validating acts of everyday racism, surely it was not surprising to learn of the hate crimes that East Asian peoples were suffering?

Despite the fact that I’d launched Black Friends to start frank conversations about race and identity, when I found myself in a situation that needed defusing, it was more convenient for me to put my true feelings to one side.

But now, under the shadow of the worst public health crisis in a generation, now more than ever we need to speak truth to power.

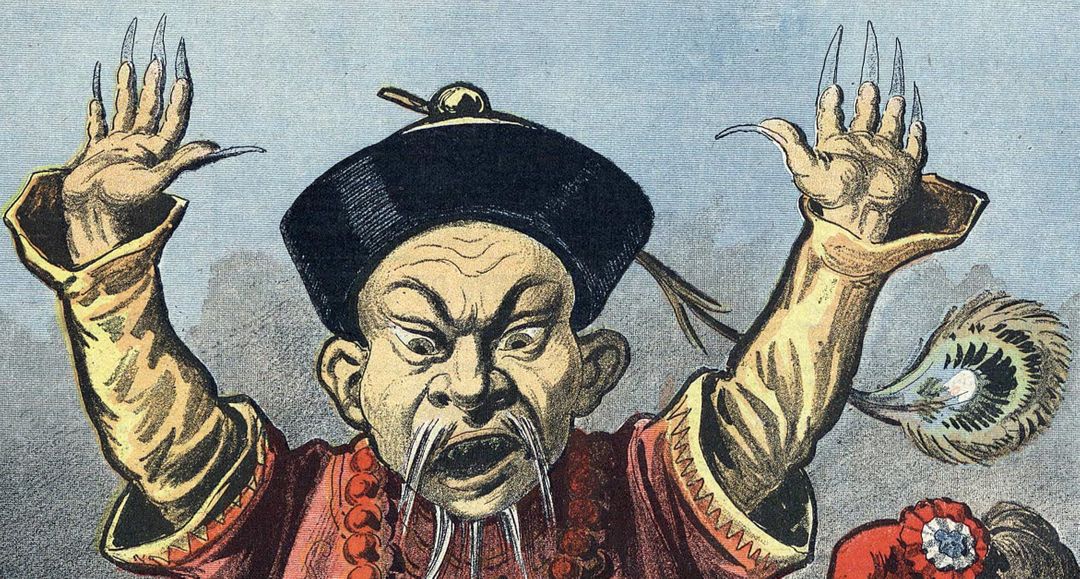

As history has shown us, infectious disease outbreaks are breeding grounds for discrimination, with minority groups repeatedly positioned as scapegoats. Whether it be the homophobia of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, or the racialized discourse that linked black bodies with disease during the recent Ebola outbreak, it’s impossible to find an example of a public health crisis that hasn’t reproduced our existing socio-cultural biases.

Worse still, if we allow discrimination of this kind to go unchecked, we could even see it mutate into crimes against humanity. Like the slaughter of over 200 Jewish communities during the height of the Black Death.

However, it’s not only the prospect of genocide or ethnic cleansing that threatens the well-being of minority groups during pandemics, and other health crises. In many cases, discrimination can have a lasting impact on the effects of a disease outbreak itself.

As various news outlets have reported, many East Asian peoples have decided not to wear protective equipment in public, out of fear of being perceived as a “carrier of disease”, and thus facing abuse.

In response, the World Health Organisation has issued governments, media outlets and key public figures with a set of guidelines that instruct them on how to curb stigma, in light of the current coronavirus pandemic.

Although, as President Trump’s continued use of the term ‘China-Virus’ demonstrates, these guidelines are all too easily ignored.

With this in mind, it appears that if we’re going to address the issue of discrimination, we need to prioritise a “bottom-up” approach if we want it to succeed.

In the same way that you and I have reconfigured our lives to fit the boundaries of our bedrooms, so too can we find the strength of character to improve upon our capacity for calling out discrimination.

My inability to call out the injustice I’d witnessed that night was a symptom of my virtue signalling. And when I reflect on my life so far, I realise that in general I’ve found it easier, and more instantly rewarding, to follow the path of least resistance.

But if my time in lockdown has taught me anything, it’s that as an individual, I have the capacity to adapt my way of life for the greater good of my community.

Going forward, I hope that we can each take responsibility for our actions and develop the courage to expose everyday injustices, like I should have done all those weeks ago.

As only by learning from the mistakes we’ve made in the past, can we change things in the present for a better tomorrow.